Here’s a little-known-fact — Bees collect 66 pounds of pollen, per hive, per year, turning the nectar into honey, using some of it for their own food and leaving lots to share with humans who have a sweet tooth.

“The number of beekeepers in Tucson and Southern Arizona continues to grow,” according to Jaime and Kara DeZubeldia of ReZoNation Farm in Avra Valley. “Since 2008, more than 350 beginning beekeepers have taken our training course every year and we’ve seen a substantial increase in demand for that training,” says Jaime.

Backyard beekeeping can be both a hobby or a way to generate an income. For Noel Patterson of Dos Manos Apiaries, it’s both.

“I was given my first hive as a birthday present to help me be self-sustaining in my backyard garden. Now I make my living off of bees, selling their honey to many of my 4th Avenue neighborhood restaurants. The product I produce in my backyard isn’t just local honey, it’s actually closer to home — it’s neighborhood honey.”

As we stand next to a couple of his hives, sampling the productivity level while slightly agitated bees fly all around us, he says, “You can raise bees anywhere there are flowers and in an urban area, there’s a lot of opportunity because people plant a lot of surface area with things that produce pollen and remain in bloom from February to December.”

As to the kind of honey a hive generates, it’s a product of place.

“We think of honey as alfalfa or clover or orange honey, but it’s more complex than that,” Patterson says. “There are as many different kinds of honey in Southern Arizona as there are site-specific ecosystems. Bees in the Tucson Mountains produce different-tasting honey than those in Oracle or Catalina or on Mount Lemmon. The kinds of honey available is limitless, constricted only by how many places you put bees and the nectar sources they can find.”

With hives in several different locations, Patterson has set up a business model where restaurants sponsor the hives, fronting him the start-up costs, and in return, they get first priority on his honey. His ultimate goal is to have a hive dedicated to each restaurant client.

At ReZoNation Farm, bees harvest from almost 100% desert plant species, everything from mesquite, palo verde, creosote, ironwood, and desert willow to rabbit bush and other seasonal sources depending on rainfall patterns. Beekeeper Jaime DeZubeldia, who also helps relocate swarms or established hives, estimates there are 2.5 million managed colonies in the United States.

“The number of hives we manage changes drastically from year-to-year,” admits DeZubeldia. “We currently manage numerous apiaries that in total represent hundreds of colonies.”

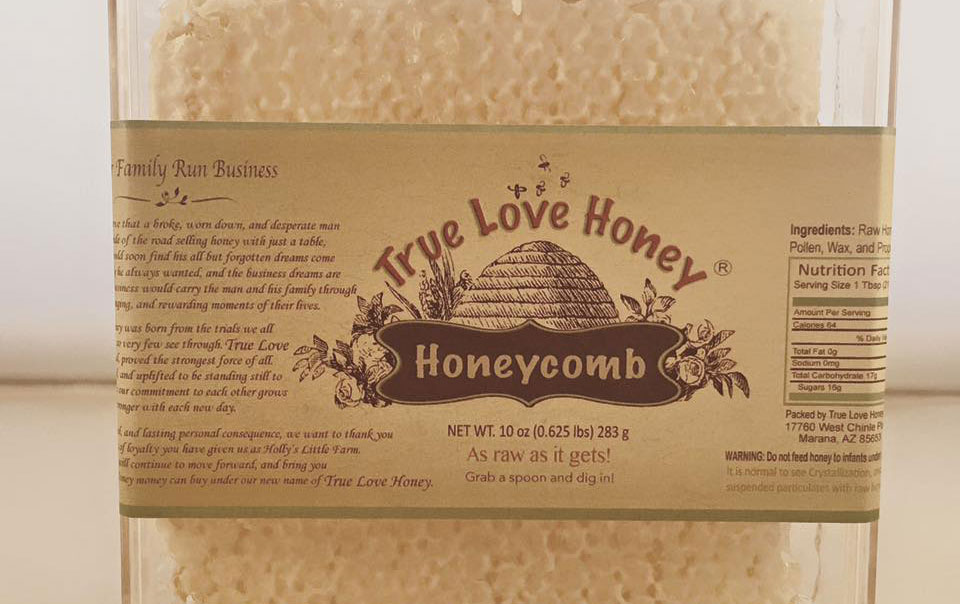

West of town in Marana is where True Love Honey collects a variety of offerings ranging from mesquite to wildflower and desert blend as well as gallberry, a high-pollen, high-enzyme product that comes from an evergreen shrub of the holly family and offers medicinal properties, especially against allergies. Previously known as Holly’s Little Farm, True Love also produces a cinnamon and raw honey they extol the virtues of — “Damn, (this is) finger lickin’ good” — according to their web page.

Products from ReZoNation are labeled simply as Sonoran Desert Honey.

“What we call mesquite honey very likely includes honey from palo verde, creosote, the acacias, and whatever else might be blooming. It’s been proven by pollen analysis that beekeepers are not completely accurate about the plant origins of the honey they bottle. Wildflower honey is more complex in terms of flavor and is not as sweet, while a (true) mesquite honey is powerfully sweet with hints of citrus.”

Asked if bees were in trouble on a variety of fronts, Patterson replies:

“It’s a complex issue and I’m not a simplistic-answer kind of guy. The way some beekeepers keep their hives is one subject for discussion, using unnatural methods of chemicals and antibiotics as is done with livestock. Then there are environmental stress factors like colony collapse disorder, Africanized bees, and the introduction of a European mite. Science hasn’t come up with one smoking gun as the factor. It’s a confluence of a number of factors.”

Concerning Africanized bees, he says bees in the wild, the feral population in our area, “is pretty much 100% Africanized and you need to be careful because they’re defensive of their hives and very good at defending their homes. They’re not aggressive, looking for a fight, but they’re good defenders and I learned that the hard way.”