Inside the main dining room of Mr. An’s, a master teppan chef pushes a cart stocked with perfectly portioned ingredients: cut vegetables for the Veggie Lover, chicken for the Flight of Fancy.

The chef stops in front of a teppan, one of a series of stovetops spaced throughout the room. He greets the guests seated across the counter, tells a joke, and then adds the ingredients to the stovetop. The meat sizzles. The air above the teppan swims with heat.

The chef twirls the spatula and clatters it rhythmically against the table. He attempts to flip a piece of chicken into the mouth of a guest, but she misses and it falls to the counter.

The atmosphere is spirited, fun, a little cheesy — almost as though it’s everyone’s birthday. The chef then slices an onion just-so, stacking the rings from large to small to form a volcano. He fills it with alcohol and ignites the tip with a lighter as flames erupt like a blow torch. The faces of the guests, wide-eyed and clearly entertained, are lit by the blue flame.

*

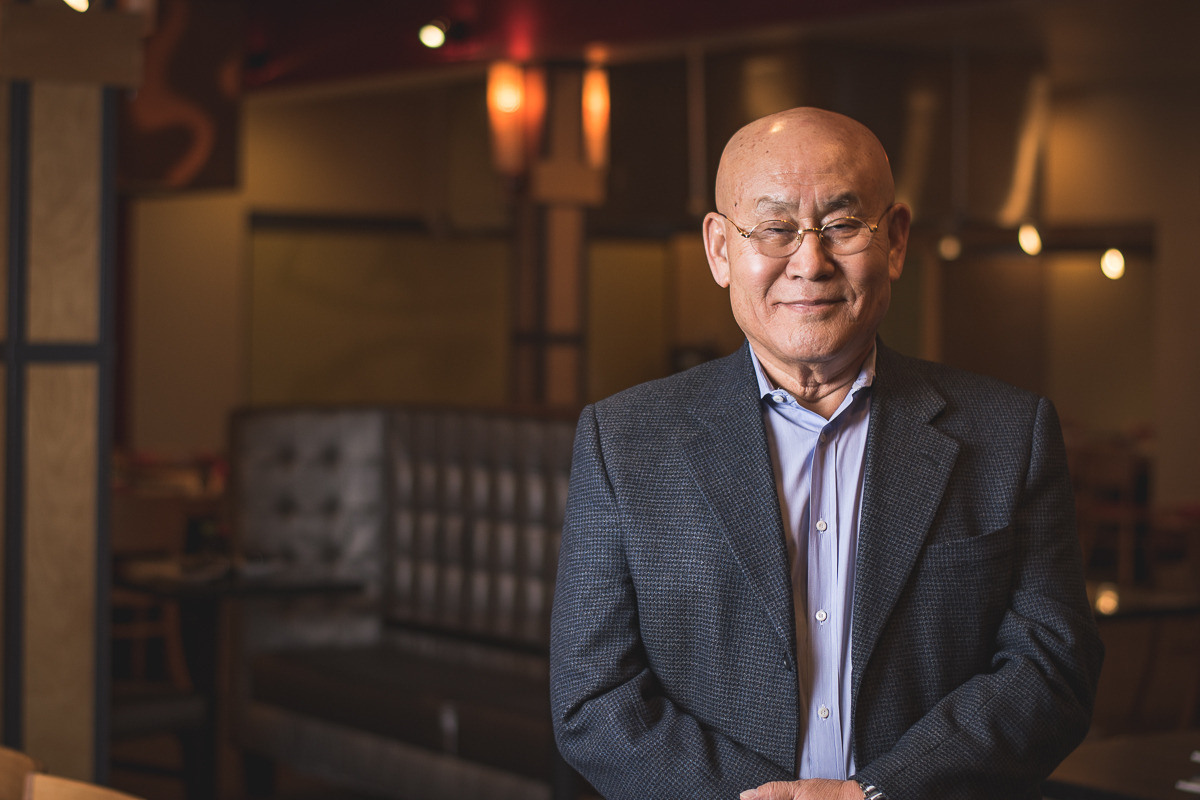

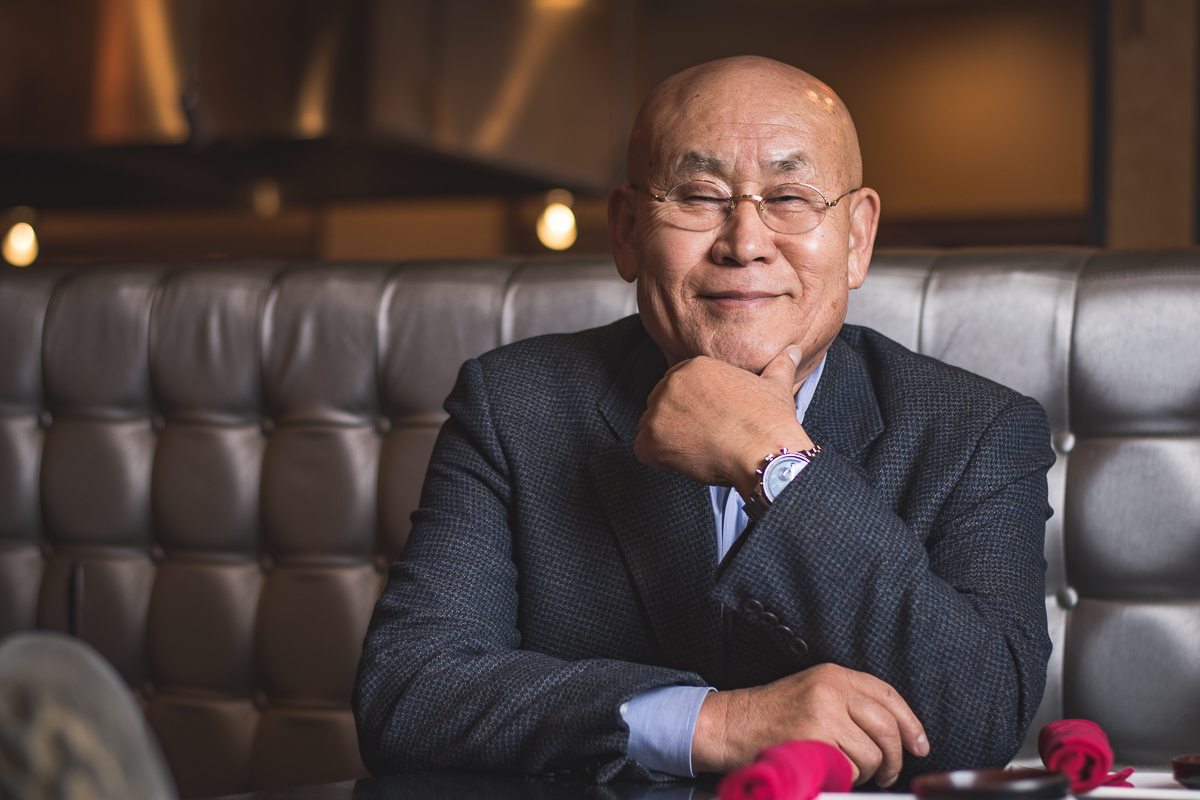

Kwang C. An was many things before becoming Tucson’s original teppanyaki restaurateur. The oldest of seven children, he grew up in rural South Korea in a small home on the border of North Korea.

After his father left to go fight in the war, Kwang worked odd jobs and sold gum and cigarettes on trains to feed the family. His youngest son, Joon says he still has a scar on his head after being thrown from a train by a conductor.

For years, Kwang saved his money in hopes of moving to the United States for better economic opportunities.

By the time he could afford the move, he was married and had two children in diapers. They chose Texas, where Kwang found work as a ranch hand and learned to speak Spanish before English.

Eventually, he was offered a construction job in Arizona. The family moved to Tucson, where Kwang worked his way up to the role of general contractor.

He and a friend started a construction cleaning company. He then opened a dry cleaning chain. And in 1983, Kwang opened the Asian restaurant Great Wall China.

In the 1980s, Kwang began hearing about Benihana Restaurant. Always the entrepreneur, he studied the concept and decided it could take off in Tucson. There was a lack of good quality Asian food in Tucson, he thought. So, in 1991, he opened eastside restaurant Sakura, which became Tucson’s first teppanyaki restaurant.

**

In 1964, Hiroaki “Rocky” Aoki took $10,000 from his Harlem ice cream truck business and invested it in a new restaurant concept.

The restaurant, called Benihana of Tokyo, was the beginning of what would become the Benihana brand and empire, featuring a blend of theater and Japanese-style cuisine prepared on griddle stovetops.

Aoki envisioned chefs who could prepare food while simultaneously joking with guests, throwing knives, and lighting fires. The concept was a far cry from traditional Japanese cooking, wherein ingredients were not wasted, farmers were thanked, and food was not to be played with.

But America was an entirely different market than Japan. Obsessed with flashiness and desperate for a show, America was drawn to the spectacle of Benihana.

During the 1980s, Benihana seemed to exceed even Aoki’s expectations. Celebrities flocked to the restaurant locations, requesting the most thrill-seeking chefs with the best knife skills and fire tricks.

In the golden era of teppanyaki, Aoki — ever the entrepreneurial strategist — expanded to 116 Benihana locations across the globe. He even introduced a frozen foods division and a series of collectible tiki mugs.

As Benihana exploded, Aoki’s fortune grew. And so did the financial feuds and lawsuits surrounding the Benihana enterprise. He entered into and dissolved various partnerships. At one point, Aoki sued four of his children, claiming they had purposefully neglected their financial obligations out of hatred for his new wife.

And all the while, America ate on, oblivious to the drama and mesmerized by the glow of the flaming onion volcano.

**

“My father never had a marketing degree or anything fancy,” says Joon An, Kwang’s third and youngest son, now general manager for Mr. An’s on North Oracle. “He just worked really hard and knew what people were looking for.”

Sakura proved so successful that in 2001, Kwang opened a second location, Sakura West, which also did very well. And then in 2005, Benihana came to town.

Intrigued by the market potential in Tucson, the company approached Kwang with an offer to purchase Sakura West. Kwang agreed to sell, but with one stipulation. The parties agreed that if the restaurant was not successful, Benihana would simply return it to the An family.

For five years, Benihana attempted to win over the Tucsonans who had been loyal to the Sakura establishments (In that time, Kwang opened An del Sol and An Express in Casino del Sol, as well as a chain of frozen yogurt stands, and an LED lighting company.)

And then in 2010, Benihana gave up. By and large, it seemed that Tucson was not interested in embracing the teppanyaki giant, preferring the local vibe and the connection to the An family that the Sakura establishments provided.

The Tucson Benihana’s location was shuttered, and the restaurant was returned to the An family. Later that year, it reopened as Mr. An’s.

**

Joon An, 26, Kwang’s third and youngest son — and the general manager of Mr. An’s — wears his many hats with the enthusiasm of a budding entrepreneur.

We are sitting in a small room off the lobby, amid the afternoon bustle before the restaurant opens for happy hour. He’s whisked away on more than one occasion to tend to an issue. Despite it all, he is almost always smiling.

He has studied the restaurant business since he was a small child. Even in utero, he was rocked inside the body of his mother as she stood and walked around the restaurant from 9 a.m. until 2 a.m. every day.

As a toddler, Joon mimicked the adults, clearing dirty plates off of the tables one at a time. By the time he was 11, he worked for his father as a dishwasher.

As he grew older, Joon worked as a host, a barback, and a busser. He cleaned ashtrays and took out the trash.

Kwang was set on teaching his son responsibility and work ethic, and that each role in the restaurant was just as important as the next. “He made me do the foundational stuff,” says Joon.

While earning a degree in International Business at Pepperdine University, Joon trained as a chef in a Thai restaurant. Upon returning to Tucson to pursue a graduate degree in business at the University of Arizona, Joon unexpectedly found an opportunity to take over Mr. An’s. His brain began to whir with ideas.

“I was so excited,” he remembers. “I said, Let’s make a chain.” But Joon says he quickly changed his mind. “The more I thought about it, I decided that’s not the reason this is here. This restaurant is more personal than that.”

Asked about his future business plans, Joon says, “Eventually I’d like to open more restaurants.” He pauses. “But this one I’d like to keep exactly the way it is forever.”

The true magicians behind the theater of teppanyaki are the master teppan chefs. Mike Meunier, 52, is the head master teppan chef at Mr. An’s. The son of a Japanese mother and an American military father, Meunier got into the restaurant business in his teens and began studying teppan nearly thirty years ago.

“The restaurant was very traditional,” says Meunier. “Most people were Japanese. They wore kimonos. And they asked my mother, ‘Don’t you have a son at home who can work?’”

“Meunier started out bussing and dishwashing at his mother’s restaurant, but after two months, he was asked to train as a chef.”

“I was 20,” he says. “It wasn’t easy. They were sticklers for details. I had to do everything the right way, the same way every time.”

He learned to set up the chef’s carts and spent time watching the other chefs cooking in the dining room. He began making lunch for the employees, a tradition that Joon also uses for bringing staff together and training new teppan chefs.

Meunier laughs when he remembers his first real table.

“It was terrifying,” he says. “As I pushed my cart out of the kitchen, I’m getting butterflies and I’m sweating. And my hands are shaking. And of course, we’re supposed to be doing a show — tricks and all that.”

He avoided performing until another chef handed him the wooden salt and pepper shakers he was supposed to be flipping in the air.

“Traditionally, teppan chefs travel,” says Joon, describing a network of traveling teppan chefs in Florida, New York, Canada, the Philippines, and Guatemala.

“We have an agreement with them. It’s just an understanding. And they have their agreements with other restaurants. They follow the season.”

But while traveling has been a tradition for teppan chefs for decades, Joon says he’s interested in offering more permanent employment packages, geared towards chefs who want to settle in one location.

“We’d like to offer an incentive to stay in Tucson and keep our restaurant feeling like a family,” he explains.

In Meunier’s thirty years as a teppan chef, he has traveled from city to city, restaurant to restaurant, though never as seasonally as some of the other chefs.

In that time, he’s perfected his showmanship skills. He would gather with other chefs after work to practice.

“We would sit around and drink beer and practice with our knives,” he says. His signature skill is a bottle trick, learned from one of his mentors. For over a year, Meunier practiced over the carpet in his apartment, learning to flip a sake bottle wrapped in layers of protective tape.

He learned to juggle salt and pepper shakers, spin forks and spatulas, flip a knife and catch it behind his head. “I’ll still do that one once in a while if people are nice enough,” he says with a smile.

*

On a Saturday night just after Thanksgiving in 2015, a driver blew a red light and slammed into Kwang’s car as he was on his way to Mr. An’s.

Joon and his brother Bin received a call at the restaurant. His brother rushed to the hospital, where Kwang had been transported unconscious. Joon stayed at the restaurant.

“I had to stay and close. And then I went to the hospital,” he says. “If my dad woke up and I wasn’t at the restaurant, he would have been mad at me.” He laughs a little, though his voice conveys how terrifying the experience was.

Two days later, Kwang woke from his coma with head injuries and broken ribs. Joon says his father does not remember anything in the three days prior to the accident.

He spent two days in the hospital and it took him months to fully recover, with ongoing headaches and pain.

Despite his injuries, Kwang returned to work almost immediately. Joon says, “We were able to keep him out of [the restaurant] for a week, maybe two weeks tops. There’s really no stopping this guy.”

The accident rattled the An family. Joon says it put a lot in perspective and made the restaurant and his father’s legacy even more important.

Despite the car accident, Joon says his father has not slowed down. He is committed to his work, to the numerous businesses that he owns. “He needs to take time, but he doesn’t like to,” says Joon. “Sitting at home and watching TV drives him crazy.”

Even Joon says that teppanyaki’s golden hour has come and gone. “It’s not dying, but it hit its boom awhile ago,” he explains. “There used to be a Benihana every three blocks. It’s dying out a little.”

Still, he says there’s an undeniable allure to teppanyaki, especially for those looking for a flashy and engaging way to eat and who don’t mind that it strays from traditional Japanese cuisine.

“The only traditional element of teppanyaki is the use of fresh ingredients,” he says. (For eaters interested in a traditional experience, stick to Mr. An’s sushi, prepared by a master sushi chef who has 40 years of traditional sushi training.)

But any food has the potential to bring people together. And because teppanyaki provides the rare opportunity to dine with complete strangers, Joon feels that it delivers a connection between people that is often missing in the restaurant world.

“Because you’re sometimes sitting with people you don’t know, you’re forced to engage and interact with other people,” says Joon. “And by the end of the meal, everyone’s happy and you’ve met interesting people.”

It is this element of connection between people over food that Kwang seems to have especially understood and championed.

“There’s something about what my dad does,” says Joon, shaking his head.

“And his legacy is in how many people he has touched since he’s been here in Tucson. You can’t even walk down the street with him without people recognizing him. He has touched so many people, and he doesn’t ask for anything back. I’m working really hard to learn from him.”

Mr. An’s Teppan Steak + Seafood is located at 6091 N. Oracle Rd. For more information, visit mrantucson.com or call (520) 797-0888.