In the year and a half that I’ve been running Tucson Foodie, I’ve spent most of my time connecting to people — restaurant owners, chefs, artisans, etc. But food systems aren’t just made up of people, and lately, I’ve been feeling a pull to connect to the non-human parts of our local food system.

I’m starting with water.

Water is so deeply connected to food that it just makes sense for Tucson Foodie to talk about it. And in the dry, arid desert landscape of the Sonoran Desert, water is always a hot topic, and increasingly so.

The first stop in my journey to connect myself to our local water systems and better understand how it has, does, and will impact our food systems, is an interview with Lisa Shipek. Shipek co-founded Watershed Management Group (WMG) and has acted as its Executive Director for 17 years.

I was familiar with WMG before I interviewed Shipek. In 2018, I took a class on rainwater harvesting at WMG in order to qualify for the $2,000 reimbursement program offered by Tucson Water. I used the rebate to install a rainwater tank and gutters on my home. I had moved to Tucson a few years prior and… well it was just time. Rainwater harvesting is just a very Tucson thing to do.

And there’s a reason for that. It takes a tremendous amount of energy, infrastructure, money, etc. to import Colorado River water. However — and this is a fact that’s difficult to measure but of which I’ve been assured is true by multiple local water experts — enough rain falls in Tucson to completely satisfy both commercial and residential needs.

Bringing awareness to this reality is Shipek and her team at WMG, which offers a wide range of resources, classes, and more to help Tucson residents (like you!) capture the rain that falls onto your property. You can use it to water your plants and even provide your family with a clean, safe source of drinking water.

That’s right — you can drink rainwater.

In fact, on Friday, September 22, you can join me at the Watershed Management Group 20-year anniversary party, where Tucson Foodie team member Max Wingert will be serving up two delicious cocktails made with filtered rainwater from WMG’s demonstration site at 1137 N. Dodge Blvd.

Me: What’s the biggest shift you’ve seen in your 17 years in terms of people’s relationship with water?

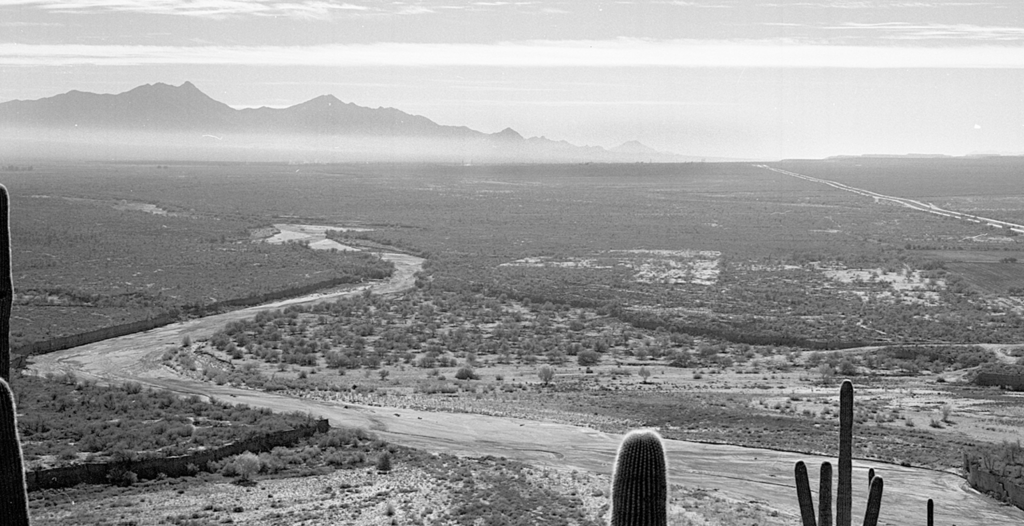

Shipek: One of the biggest changes I’ve seen is people’s openness to restoring our rivers. When we first started our work we were very focused on what people can do in their backyards, which we still are. However, there’s always the bigger goal of starting in your backyard to have an impact on the greater watershed. What you do in your yard impacts the larger watershed we live in, including our rivers.

When we first started talking about the idea of restoring flows and restoring rivers here in Tucson people would look at us a little cross-eyed, which we still get. There wasn’t really an overall openness to the idea and so we put out these River Restoration visions — these illustrations back in 2015 — just to start getting people to imagine something different.

When we think about the Sonoran Desert, what comes to mind? So often it’s a dry and dusty landscape or dangerous flooding. So, how do we start to see these spaces in a different way, and understand and feel a connection to them? That’s the mental or cultural shift I’ve seen happen that I’m excited about.

Me: Do you think this was more of a discovery you made — the idea of using rivers as a way to motivate people? Are people more interested today in replenishing our rivers because of a broader cultural or mindset shift, or do you think WMG sparked the movement by intentionally choosing to focus your promotional campaigns on rivers?

Shipek: As someone who does marketing, I appreciate your question. I’m not sure because we have people in Tucson who have lived here forever and have multigenerational families, we have people who just showed up yesterday, and we have people who’ve lived here for five years. I think it kind of depends on how long you’ve been connected to this place, and what other water connections you bring with you.

We’ve had long-term drought. We’ve had essentially mostly dry creeks and rivers for the last 50 to 100 years. This connection to the idea of flowing rivers is almost like a lost place-based connection that we’re hoping people are excited about restoring.

But there’s also a big portion of people that just don’t expect to see that in the desert. They show up in Tucson and they’re like, “Oh, yeah, it’s dry.” That’s just the way it is and probably always has been. So, it’s a good question. I think people are very motivated to do water conservation in their backyard, and I think some are also motivated by the idea of overall watershed restoration.

The second someone goes out to see one of these riparian areas, their mindset shifts. Until you’ve actually experienced it, that excitement may not be there. There’s a fundamental shift once you get out onto that creek, walk and see the flow, and experience the large cottonwoods and willows like those at Lower Sabino Creek, Middle Tenque Verde Creek, or Ciénega Creek.

Me: I was looking at a visual that shows how Colorado River water is used. Most of it is growing food to feed livestock. But you’re mostly focused on residential water use, right? What do you do outside of that?

Shipek: It’s more about water connection. Whether that’s someone you know, residential or commercial, or whoever happens to have any kind of exposure to any of our events or activities. Water stewardship — a better understanding of how our watershed works and where our water comes from. It’s interesting because the watershed is the land that water falls onto and it all drains to the same place. It’s a framework and a connection to that local place — to what’s happening. So, the connection between land and water is in place and the plants, animals, and people are all in the same space — this watershed.

Me: Is WMG’s role primarily educational?

Shipek: We like to educate through hands-on activities whenever possible. We do a lot of free workshops and we offer professional training, too. We have a water harvesting certification we’ve been doing for a really long time, some work in advocacy, and some coalition building. Whatever we teach is something you can easily do at home, like really low-cost flow technology using nature-based solutions.

Me: What do you want our readers to know about water?

Shipek: I want everyone to know that that we can harvest the rainwater at our own homes to supply our needs. That’s what we do at the Living Lab. That’s what I do at my house. It’s actually possible that we don’t have to import water from the Colorado River.

Shipek: We have two rainy seasons. It is definitely variable, and it’s more variable with climate change, but we get rain throughout the year and, most years, it’s enough to supply our own water needs including growing food in your backyard. That’s the system I have at my house. My veggie garden gets watered from rainwater that I captured in a tank.

I also want people to know that you can drink rainwater. It’s really grounding to be able to capture rainwater here at our office or at my home, filter it, and drink it. In a lot of ways, we have the privilege of having clean drinking water as compared to other countries. But at the same time, there’s a ton of emerging contaminants that aren’t regulated that we’re constantly drinking. If you don’t know about PFAS, get educated quickly. It’s a chemical compound that’s water soluble and in a lot of products including firefighting foam and common household cleaning supplies. The EPA just started regulating it – that’s why I used the term emerging contaminant. They use this term for something that they’re just now starting to understand the dangers of. It’s a global contaminant — it’s everywhere. It’s even in the rain.

Me: If I were to start drinking harvested rainwater, how expensive or complex is putting filtering systems in our homes?

Shipek: You can treat it like filtering tap water. You could do everything from a Brita filter up to reverse osmosis. The system we have here at the Living Lab is two carbon filters and a UV filter. At the time we put it in, it was around $5,000, but it’s automated and it pulls the water up from a pressure tank, runs it through a filter, and distributes it.

In my home, I have a Berkey countertop filter and I pour rainwater into it. Berkeley filters are like top-of-the-line and can run somewhere between $250 to $400. They last forever. It filters out PFAS. If someone wants to start drinking rainwater, that’s what I would recommend.

Me: We’ve had a lot of new people come to Tucson Foodie who have moved here recently. They’re young couples, people who moved here for work, moved to escape California or Austin because of inflation, wildfires, politics, or whatever. A lot of them bought houses. What do we tell these people?

Shipek: I would call myself a foodie, hands down. My foodie angle is that I’m very interested in where the food comes from, how it tastes, and the story behind the food. I’m also a gardener and the more I garden the less I want to get food from somewhere else because my homegrown stuff just tastes better. I shop at the farmers market because it’s cool to meet the people who produce it. Food is such a tangible thing and involves all your senses. How do you get that deep connection to this place, to the earth, to the water? To me, I think there’s a ton of overlap and food is tied into all of that. Most of us yearn for connection and food is a great way to do that.

Me: What would need to happen for the rivers to flow 365 days a year?

Shipek: The rivers are like the arteries of the city. There are places we frequent, there are places that are sacred, places we care for, and places we go with our family and friends – from a little tiny arroyo up to the Santa Cruz River.

With a restored river, the city would be set up differently and we would have our floodplains back. We wouldn’t be constraining the rivers.

I envision a future where we are river centric, but we’re also walkability-centric. Our community is designed around cars right now. How uninspiring is that?

Me: The whole country is designed around cars.

Shipek: Exactly! Our whole way of understanding and being in a city is different. I think what’s beautiful about Tucson is that there’s actually a lot of places that have dirt. Sometimes people say, “Oh, it’s dusty here” but the fact that you can see dirt is actually, I think, a really cool thing. It means we have places we can grow things — it’s not all paved over. With some cities, everything’s paved over, but in Tucson there’s a lot of dirt.

Reviving the native plants here, being able to walk out the door and harvest native foods…isn’t part of being a foodie doing that?

On Friday, September 22 from 6 – 10 p.m., WMG wants you to engage your body and nourish your soul with art making, basin creating, creek hopping, and hydro-local living — all while enjoying the sights and sounds of the borderlands. Everyone is invited to this party, with activities for all ages, and no cover.

Advanced registration is required for this event — they will not be accepting walk-ins. You can register anytime before the event online. During the registration process, there’s an option to donate to WMG, which directly supports their community conservation programs. Their goal is to raise over $100,000 to support their free, community programs.

Learn more about the anniversary party.

Watershed Management Group is located at 1137 N. Dodge Blvd. For more information and to register online, visit watershedmg.org.

Tucson Foodie is a locally owned and operated community. Thanks to our partners and members, we are able to offer paywall-free guides and articles. We value your support and invite you to become a Tucson Foodie Insider today.

Head Foodie